ARE WHITE PEOPLE USING BLACK ENGLISH WORDS BEING LIKE ELVIS STEALING ROCK AND ROLL?

People think so, but they should consider the larger picture.

A little while ago, a Saturday Night Live skit depicted a multiracial group of teens communicating in what was depicted as “Gen Z slang,” with the doctor they were talking with having to “translate” his thoughts into it to communicate with them.

A lot of people didn’t like it, because the slang in question was mostly of Black English origin. The complaint is that the skit was denying the black roots of these terms, and instead ascribing them to Americans in general – i.e. (shudder) white persons. As in, yes – the problem was cultural appropriation.

As I write, there are still people grousing on social media in the wake of that skit about whites “stealing” black language, with a leitmotif being that we should apply our N-word taboo more widely. To wit, many propose that whites should not be allowed to use Black English terms because they are “ours.” Many who haven’t outright proposed this give the notion Likes, which suggests that a considerable group of people – and from what I can see, quite a few of them are white – concur with this line of reasoning.

Let’s break this down. To do so we must understand the sorts of terms in question. The SNL skit included, among others, yo, bestie, vibes, feels for feelings, salty for irritated, bro / bruh and no cap for “I’m not kidding” (as in, these are actual whole gold teeth, not golden caps on teeth).

Is there a case that you should only use these terms if you’re black, or that if you use them as a white person you should “do the work” of thinking hard about whether or not it is problematic (blasphemous)?

* * *

The issue here is an idea that white and black Americans can interact as richly as they do without coming to share aspects of their way of speaking.

That proposition itself requires two questions.

1) Is there a historical precedent where people interact richly but keep their speech varieties completely separate?

The answer there – I venture as a specialist on language contact – is no. There is no language that is not bedecked with words, sounds, and grammatical elements picked up from other languages and dialects spoken nearby (or even far away) over time. White and black Americans interact, date, marry, have kids together, partake of much of the same culture, and even come together enjoying a form of music deeply ensconced in Black English. The chance that this situation will contravene the hitherto universal nature of language hybridity is nil. To put it coarsely, languages fuck, as do dialects of a language. You can’t stop it.

2) Is there a case that even if this is the way it has been, that it would be a moral advancement if we tried to put a stop to it now?

That is, because this is about black Americans and the injustices we have suffered, we might try that banning the “appropriation” of Black English words and expressions is a New Idea, a new “right,” as it were, possibly to be applied to other groups as well.

That is a rich notion, and here is why it fails as well.

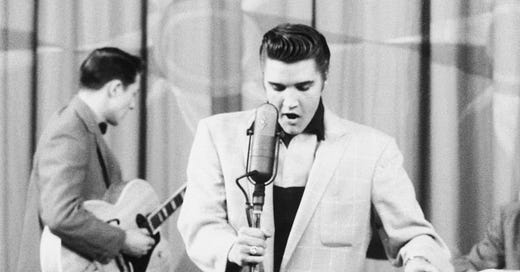

First. Whites have thoroughly “appropriated” black American music. And there is a conversation to be had about the injustice of Elvis Presley becoming a multimillionaire aping a vocal and kinetic style that black people had originated (and frankly did better, if you ask me). But overall, who among us wishes white people had never taken up ragtime, jazz, rhythm and blues, or rock and roll? I assume there are some who could really wish there had never been Benny Goodman, Buddy Holly, the Rolling Stones, or Eminem and I mean that. But this would be a radical proposition held ever by only a sliver.

If so, why the brouhaha about language?

Second. An objection might be “But if they’ve taken our music, can’t they leave us our language?” But that runs up against two things.

One is that it isn’t as if there has been some mysterious sequentiality involved, where whites first carefully “took” our music and are only now getting to the language like someone who eats their meat first and then gets to the vegetables. Black language has been affecting white language in America forever.

Much of what constitutes Southern white speech is inherited from the speech of black Southerners, such as the grand old “r-lessness” – a Southerner who says (or these days, increasingly, used to say) “fath-uh” for father was doing that because slaves, speaking languages where syllables didn’t end with r or other consonants, said it that way. Was this “appropriation”? Or, any white person who talks of someone being “hip” to anything is using what began as black slang, as well as usages such as dude and man to strike a colloquial tone.

The issue is that today we are taught to despise this jumping of the fence instead of seeing it as ordinary.

Then second, whites today are using but a sliver of black slang, not the body of it. Black American slang is rich indeed, and for every bruh or yo, there are plenty of other terms no white person uses and few have even heard of. It is getting to the point that Black English terms have been catalogued over quite a few decades. One might consult a source like this book to see how rich the slang was around 50 years ago – and consider how very, very few of these words were ever “appropriated” by whites. Even further back, Zora Neale Hurston charted some Black English expressions, which would have seemed vividly real to black contemporaries but leave almost anybody scratching their heads now – clearly whites took no interest in them. “You sure is propaganda!” – any takers today? “I’ll beat you till you smell like onions!” – I kind of wish people still said that, but what I know is that whites didn’t feel that way. The situation is the same now.

Our real question is: Why can’t whites take on some Black English terms as an affectionate salute?

Third. We are so often told that it’s stereotyping to assume that there is a such thing as black cultural traits anyway.

Or, more precisely, there are two schools of thought. One is that what black people share is oppression from whites but that otherwise we are a magnificent diversity of personhoods.

Another is that to be black is to be oppressed by whites as well as to be disinclined to be precise or on time, to be goal-oriented, and to value writing over chatting.

But note that these things do not include a way of speaking. Last time I checked, the woke black person bristles to see black people depicted on stage speaking perfect Black English, out of an idea that this is mere “stereotyping.”

But if it’s respectable to insist there is no such thing as a “black” English (and pretend that Black English is just black people speaking Southern English), but also respectable to insist that whites have no right to “steal” Black English, then observers might be pardoned in letting it all go and saying “Let’s you and him fight.”

Fourth. Really, insisting that white people not use Black English words and expressions to any extent is asking for something which, whether you like it or not, will never work. If you like fighting unwinnable battles out of a sense that where race is concerned, doing so puts you ahead of the curve and will get you brownie points for getting into Elect Heaven, go to town.

But really, calls to change how language is used almost never work. Talking is rapid, largely subconscious, and more deeply ensconced in subtle, roiling, primal and self-generating currents of human psychology than we tend to know. Example: perhaps the one “blackboard grammar” rule that has truly influenced the way people talk ordinarily has been the one saying that it’s wrong to say Billy and me went to the store. The idea that me cannot be used as a subject is something some people came up with in the nineteenth century and makes no sense whatsoever. This isn’t the place for that rant, but note that even though we all try so hard to observe this senseless rule (yes, senseless – again, try here), so very many get stuck in between you and I, which breaks the “rule” supposedly so important.

Insisting – say, amidst our “racial reckoning” – that it’s blasphemous for white people to say bruh, yo, or feels will be about as successful as the between you and I business.

* * *

In light of the above, I suggest we return to intuition here. Yes, even on race, sometimes intuition makes sense, and not just the intuition that white people are racist.

Namely, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Whites talk increasingly more like black people in America as a sign that whites and blacks are more comfortable together socially than they once were.

Yes, racism still exists. But getting past it will happen in increments. What is the progress in insisting that the increments, when they reveal themselves, don’t matter?

And whatever your other discomforts are with “Gen Z” using some black slang, your question must be whether it should be socially proscribed in light of what I have noted above as issues that cannot be waved away. Is the discomfort something you could honestly back with a confident pox on linguistic sharing amidst the broader context of what we are actually seeing?

And while we spontaneously imagine the SNL skit being written by a bunch of white people in a room eating takeout, a la what we saw on 30 Rock and read about in memoirs about SNL, the skit in question was written by Michael Che, who is a young black American man. He has been mystified by the idea that he was depicting non-black people “appropriating” something – and I must admit I’m kind of glad he was. He is the future, I hope.

You missed the fact that “black” music [gospel, jazz, et al.] builds on *western* harmonic and melodic structures — NOT “African” ones. The appropriation goes both ways. That is, jazz — for example — is a *mixture* of European and African influences.

I’m a 74-year-old white woman who’s lived in East Harlem for the last 10 years. When I have casual conversations with Black people in the neighborhood who are speakers of AAVE, I often adapt my cadences and language a little to their speech. (For instance, I might say “you have a blessed day, now” to another woman, which I’d never say to a white woman.) Similarly, although my Spanish is very limited, I try to toss a little in when I talk to Latino neighbors. Not only do I enjoy this, I see it as a matter of fitting in and being respectful in a community where white newcomers, who are the minority, may ignore them. What I hear most often from locals, whether they know me or not? “You get home safe, now.”